If you were hoping for some relief from stratospheric memory pricing, don’t hold your breath. DRAM prices aren’t expected to peak until at least 2026, TechInsights analyst James Sanders tells El Reg.

DRAM is an incredibly broad category and includes everything from the DDR5 found in desktops and servers to the GDDR7 and HBM used by graphics cards and AI accelerators.

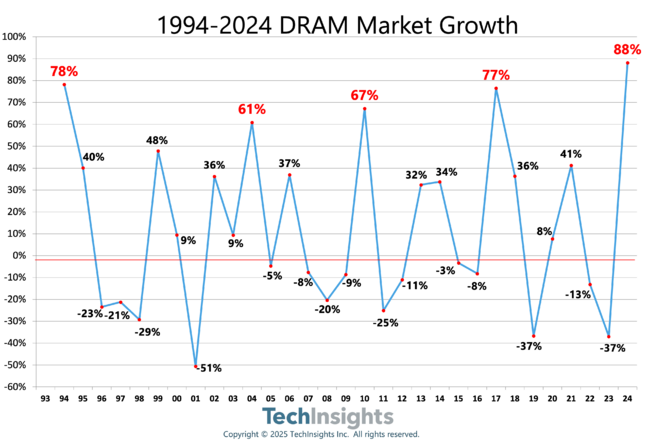

The market is also notoriously volatile and prone to wild swings in pricing, spiking as inventories are drawn down and cratering as new capacity is brought online, Sanders explains.

According to TechInsights, memory pricing was already on the rise in 2024, growing 88 percent from a rather steep valley the year prior. Based on previous DRAM booms, one might expect it to grow at a slower pace in 2025, before contracting in 2026 or 2027.

However, Sanders tells us that’s unlikely to happen this time around. “I think we’re looking at the peak in 2026,” he said, adding that even then he only expects DRAM prices to settle in 2027 before rising again in 2028.

So what’s to blame for the sky-high memory prices? Well, as you might have already guessed, it’s AI. But it’s not the full story. Timing is also a factor.

According to Sanders, the AI boom kicked off at what was very possibly the worst time for memory vendors. “This demand started in the Valley for the DRAM industry. That makes financially trying to build additional capacity really challenging,” he said. “If you’re rushing, the time to bring additional capacity online is about three years. It’s a quirk of bad timing that’s led to the circumstances that we’re in now.”

More realistically, DRAM vendors, like Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron, are looking at four or five years to ramp production at a new fab, at which time the market conditions could have changed considerably.

Timing is also why the DRAM shortage is hitting some harder than others. “The consumer market is in the stratosphere, whereas OEMs are about a year out, and they’re not getting heartburn quite yet,” he explained.

In other words, giant hardware vendors like Dell and HP aren’t suffering nearly as much because they tend to lock in their orders early, while smaller vendors are at the mercy of spot pricing. In fact, ahead of the Christmas holiday, G.Skill, a supplier of memory for gamers, issued a statement pinning the blame for jacking the price of its products on AI.

“DRAM prices are experiencing significant industry-wide volatility, due to severe global supply constraints and shortages, driven by unprecedented high demand from the AI industry,” the company wrote. “As a result, G.Skill procurement and sourcing costs have substantially increased. G.Skill pricing reflects industry-wide component cost increases from IC suppliers and is subject to change without notice based on market conditions.”

What’s more, AI is driving demand for a different class of memory that, unlike traditional DRAM, isn’t much use in most consumer applications.

“This is a little bit different from previous boom-bust cycles, in that wafers are being redirected toward HBM and away from consumer-grade memory,” Sanders said.

High-bandwidth memory consists of multiple layers of DRAM, which as the name implies, enables it to achieve much higher bandwidth than a typical DRAM module you might find in a notebook or RDIMM. With HBM3e, it’s not uncommon to see a single 36 GB chip deliver 1 TB/s of bandwidth. By comparison, a single 8 GB LPDDR5x module might be able to achieve 140 GB/s.

HBM is used almost exclusively in high-end datacenter GPUs and AI accelerators, like Nvidia’s B300, AMD’s MI355X, or Amazon’s Trainium3. Because of this, Sanders says, the memory market is rapidly diverging.

“Because there’s no consumer demand for HBM — the consumer market can’t bear that price at all — it is really becoming two markets that are detached from each other,” he said.

Memory vendors are currently in the midst of a memory transition as they prepare to ramp production of HBM4 modules, which will power chips like Nvidia’s Vera Rubin and AMD’s MI400s starting next year. Initially, Sanders says these chips will command a price premium.

And while TechInsights does expect the memory market to settle in 2027, it won’t last. As you may recall, Nvidia plans to cram 576 Rubin-Ultra GPUs each equipped with a terabyte of HBM4e memory into a single rack starting in, that’s right, 2027.

This might explain why Micron CEO Sanjay Mehrotra recently told investors that due to strong AI datacenter demand, “aggregate industry supply will remain substantially short of the demand for the foreseeable future.”

Not that he’s really complaining. While end customers are grappling with memory prices that have gone up 3x in just a few months, the memory fabs are raking in the cash. In Micron’s Q1 2026 earnings call this month, the company saw revenues rise 56 percent while net income more than doubled from $1.87 billion this time last year to $5.24 billion.

And while memory vendors may now have the capital necessary to finance additional fabs, it’ll be at least three more years before they enter production. And even when they do, the bulk of capacity is likely to be allocated toward HBM and other enterprise products.

One wildcard in all of this is China’s CXMT, Sanders explains.

“CXMT doesn’t necessarily play by the same set of rules that everyone else does,” he explained.

For one, they don’t have any meaningful HBM output at this time. Second, many had expected the company to focus heavily on DDR4, but instead, Sanders says the company now appears to be transitioning to DDR5.

Today, CXMT isn’t a very large player in the DRAM business. It certainly doesn’t help that the company is subject to United States export controls. Despite this, TechInsights expects the company to grow considerably by the end of the decade from five to 10 percent of the market, which should in theory help grow the supply of DDR5 overall. ®